According to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS), in their 2011 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting and Wildlife-Associated Recreation report, there are approximately 13.7 million hunters in the United States and nearly 71.8 million wildlife watchers1.

Of those 13.7 million hunters, only 2.6 million hunt migratory birds and only about 1.3 million hunt waterfowl. Over the last 15 years, the average number of Duck Stamps sold per year was around 1.5 million, contributing an average $25 million to wildlife refuge wetland habitat purchase and leasing each year2.

These figures show that less than 10 percent of all hunters buy the Duck Stamp and that would be the ones required to buy it to hunt waterfowl. So the other approximately 200,000 Duck Stamps are purchased by collectors and other non-consumptive users of the refuge system.

Now, to be fair, of those 71.8 million wildlife watchers I mentioned earlier, only 19.8 million observe wildlife away from home and 12.4 million are wildlife photographers. So, if only 10 percent of those folks that observe wildlife away from home bought a Wildlife Conservation Stamp at our proposed price of $20, we could raise another $39.6 million for our National Wildlife Refuge System!

This is simple arithmetic. Even if only the same percentage of people who observe wildlife away from home bought a Wildlife Conservation Stamp (and obviously we think the number would be much higher than 10%), we could raise over 150 percent of what is currently being raised by waterfowl hunters. Is this a no-brainer or what?

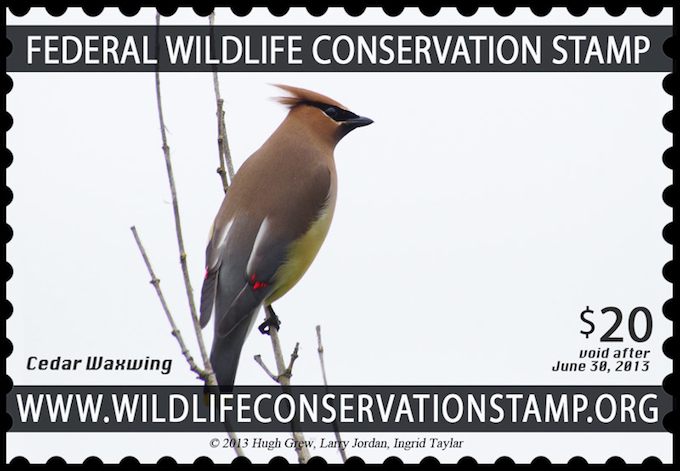

We need a Wildlife Conservation Stamp that non-consumptive users of our National Wildlife Refuge System will be proud to buy and would more than double the income for our refuges.

The 2013 – 2014 Federal Duck Stamp was issued yesterday and I wrote a post on the occasion over at the Wildlife Conservation Stamp website. Please go check it out and let me know what you think about our proposal.

To throw some more numbers at you we are also only 220 some “likes” away from 5,000 on our Facebook page, so if you haven’t done so yet (and I have no idea why you wouldn’t) like us when you visit our Facebook page!

References: 1USFWS National Survey, 2US Fish & Wildlife Service

Black Swift (Cypseloides niger) on Nest photo Wikipedia Commons by Terry Gray

Black Swift (Cypseloides niger) on Nest photo Wikipedia Commons by Terry Gray

Social Media Connect