The Common Raven (Corvus corax)

Any questions?

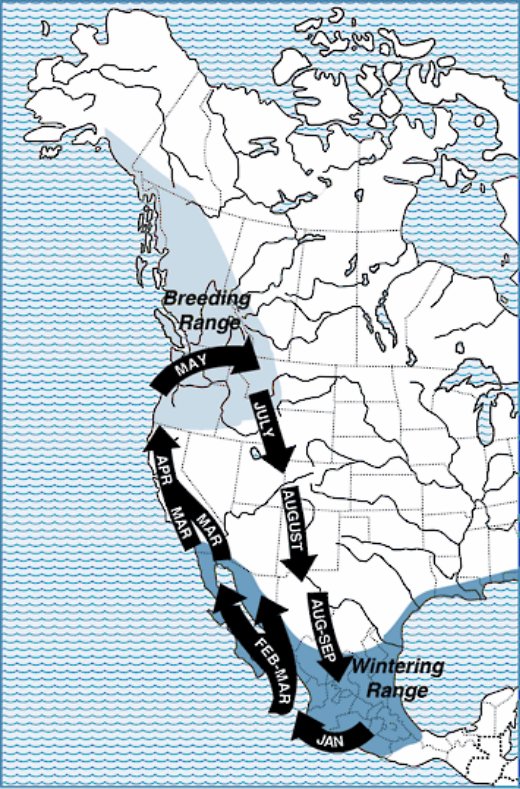

The Rufous Hummingbird (Selasphorus rufus) visits my home every year about this time.

Of course the males come first to establish territory.

According to Macauley Library’s migration map the overwhelming breeding activity for this species occurs north of the state of California.

The thing is, I have females that have been hanging around also. I think their breeding range may be moving South. This is a photo of a female who showed up in August of 2012 with some juveniles.

I guess we will find out as the eBird maps change in the future, but until then, here is another photo of one of the males hanging out here in Northern California.

And a video of him taking a shower in the rain.

OK. You probably know that I live where we have many, many woodpeckers. One of the most abundant woodpeckers in Oak Run, where I live, is the Acorn Woodpecker (Melanerpes formicivorus).

The photos above and below are an adult male Acorn Woodpecker hanging on a hummingbird feeder at the University of California Hopland Research and Extension Center where I attended a meeting back in February.

You may also be aware that I have been feeding hummingbirds at my home for over thirty years now. During all these years I have never had woodpeckers of any species feeding at my hummingbird feeders, so I found this very odd.

This is a close-up of a male with his tongue in the feeder. Obviously his beak won’t gain access to these feeders.

A couple of female Acorn Woodpeckers were not going to be denied their turn either.

These woodpeckers were very adept at feeding from these hummingbird feeders and several of the people I spoke with at the meeting told me they had seen this behavior before.

Odd I say. What say you?

As a side comment, it should be noted that these hummingbird feeders have not been properly maintained. You can see the black spots on the inside of the feeders. This is most likely black mold. It is dangerous to hummingbird health and can actually kill the birds. If you don’t know how to properly clean your hummingbird feeders look here.

The Osprey (Pandion haliaetus) at Anderson River Park in Shasta County have been nesting atop a soccer field light stand for over 17 years. The problem is that they build the nest right on top of the field lights. This becomes an issue when, every four or five years the light bulbs need to be replaced and the nest can be destroyed in the process.

One of my wildlife rehabber friends had received a legacy gift and contacted me regarding the prospect of building a nesting platform to place at the top of the utility pole. This would allow the Osprey to safely nest above the bank of lights, thereby keeping their nest intact year after year, with no interference from the maintenance crew.

I, of course said, “what a great idea!” I found an excellent plan for the platform (shown below) from the International Osprey Foundation and built it in less than a day. It is a 40 x 40 inch box which I modified using all 2 x 6 inch pressure treated lumber.

Before building the platform I contacted the Anderson City Public Works department to discuss the possibility of actually putting up the platform and got the OK. We obviously wanted to get it up before the Osprey arrived and were able to install it on January 31st.

This is an 86 foot utility pole so a lift was rented and the excellent workers from the City of Anderson Public Works department generously gave their time and expertise to the project.

Having never seen an Osprey nest close up, I asked one of the installers to take some photos of the nest before removing it and placing the nesting material in a bin to be put back into the new platform.

The shape of the Osprey nest changes during the breeding cycle. During incubation the nest is distinctly bowl-shaped. After hatching the nest flattens out, but a rim of sticks is maintained, sometimes by the young themselves, while the young are beginning to move clumsily about the nest. In the last weeks of the nestling phase, the nest often becomes completely flat1. Note the large sticks and bark.

Here’s a shot of one of the installers placing the nesting material back into the newly installed nesting platform.

About four weeks after the install I went back to the park to see if Osprey had shown up. I found one bird perched inside the platform!

However, there were also a pair of very vocal Red-Shouldered Hawks (Buteo lineatusin) in a nearby tree.

Apparently they were interested, for whatever reason, in the nesting platform as well.

A week later when I returned, the platform was now occupied by a pair of Osprey!

I observed them for over an hour but never saw them bring in nesting material, although there is obviously new sticks in the nest. The Red-shouldered Hawks were still hanging around but this day, the Osprey pair were involved in mating and the hawks were vigorously chased away by the male Osprey.

Osprey pairs copulate frequently, on average 160 times per clutch, but only 39% of these result in cloacal contact. Pairs average 59 successful copulations per clutch, starting 14 days before, and peaking a few days before, the start of egg-laying1.

Pairs copulate most often in early morning, at the same time as egg-laying1.

As I returned a couple of weeks later, the first thing I noticed is that there has been much more nesting material placed into the platform and the male was bringing in more and arranging the sticks.

After trimming and arranging these large, long sticks, the male Osprey took off and the female did some rearranging.

The male soon returned to a nearby utility pole on the opposite side of the soccer field with a rather large, what looks like a trout.

He ate about half of the fish, starting at the head, before carrying the remaining portion back to the platform to share with his mate.

References: 1Birds of North America Online

Social Media Connect