Another bird guide book? Is that what you’re thinking? NOT! This is actually an illustrated checklist.

What’s the difference? That is what I was wondering until I received my copy of Birds of North America and Greenland by Norman Arlott. Another excellent birding resource from Princeton University Press.

I own several “field guides” for birds by several different authors and publishers, most are too big to carry in the field. This checklist is small, compact and well illustrated. It may not fit in your jeans pocket but it will fit in the pocket of your cargo shorts or pants!

What do I like about the way this book is organized? It has a three page table of contents for quick reference to the 206 pages of bird “field notes,” distribution maps and color plates, followed by an index listing birds by their common names and scientific names, just in case you are searching for a specific bird or species.

I love the way the pages are presented with the field notes, voice, habitat and distribution of each species on the left side and the color plates on the right, like your typical field guide. Here’s the difference.

The field notes are a condensed version of most guide’s descriptions, but the color plates on the adjacent page show several species next to each other on the same page, allowing the user to quickly compare one species to another.

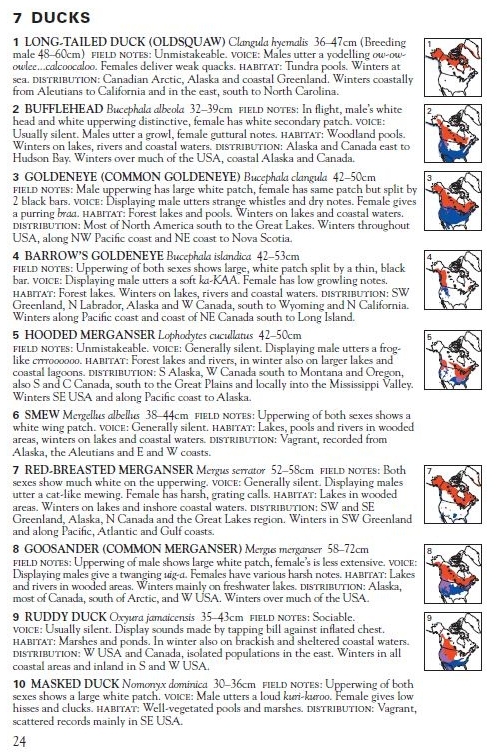

Birds are also grouped together by family. Here is an example of one of the five pages of “Ducks”

You can see that the field notes are not quite the same as a description offered in a field guide. For instance, the field note for the Long-tailed Duck is simply “Unmistakable” (see above). I like the fact that Norman also included the “old school” names of many species like Oldsquaw and Goosander.

You can see that the field notes are not quite the same as a description offered in a field guide. For instance, the field note for the Long-tailed Duck is simply “Unmistakable” (see above). I like the fact that Norman also included the “old school” names of many species like Oldsquaw and Goosander.

But look at the way the color plates are arranged. In my opinion, an excellent way to distinguish one species of duck from another in the field. Plus all a beginning birder would need to know is that they are looking at a duck to find it on one of the five “Duck” pages.

You probably noticed that the distribution maps are tiny (these images display actual size on my laptop computer) but they are good enough to realize that if you are in Florida, you are not looking at a Common Merganser!

Following the table of contents and before getting to the species description pages, there is an introduction and some information on nomenclature used in the book. How to use the information and distribution portions of the pages is included here as well. There is also a map of the region covered (North America and Greenland) as well as a rudimentary, graphic page on bird anatomy.

Do I think this is an appropriate book for beginning birders? Very possibly yes. Like I said, the color plates are arranged so even a novice bird watcher could find the species they were watching if they knew what family of birds they were looking at.

The eagle, osprey, kite, hawk and falcon pages also have these raptors shown in flight from below. A very helpful addition for beginning birders.

As a more experienced birder, I think this illustrated checklist is an excellent choice for the field. It can be used as a quick reference by color plate and field notes.

Take this field note on the Olive-sided Flycatcher for example, “makes flycatching sallies, often uses the same perch for weeks.” I didn’t know that!

If this review isn’t enough to convince you to buy this book, try the fact that you can get it at Amazon for a mere $10.63. Come on, this is probably the best deal in town!

Social Media Connect