Mallard Drake (Anas platyrhynchos) photos by Larry Jordan

The Mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) is the most abundant duck species in North America1. I mean, we see these ducks everywhere! But just because they are common (for some folks around the world) doesn’t mean they are not beautiful and deserved of our attention.

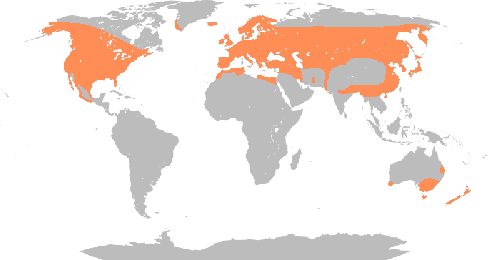

This is the worldwide distribution map for the Mallard.

Notice the Mallard drake pictured above (click on images for full sized photos). His characteristic iridescent green head, seen as bluish or purple in certain light, the white neck ring, yellow bill, orange legs and that curly black tail make him easy to identify.

The female is not quite as easy to identify, having similar characteristics to other female dabbling ducks, but she sports a bluish speculum with noticeable white borders on the leading and trailing edges, distinguishing her from any other species.

They usually begin nesting in March but I stumbled upon this female, well hidden, sitting on her eggs at the beginning of June. This is a typical ground nest for the Mallard, hidden among tall vegetation and grass.

Once she has completed laying her clutch, the female will incubate the normally 10 to 12 eggs for 26 to 29 days, covering them with down when away from the nest. The ducklings will all hatch within a 6 to 10 hour period, usually during the day1.

It takes about 12 hours for the precocial duckling to dry and begin moving around the nest. They usually leave the nest the morning after they hatch, the hen vocalizing up to 200 times per minute1 as she leads her brood to nearby water.

The ducklings stick close to mom as she is their only protection until they can fly at around two months of age. This mamma duck brought her brood onto the shore of Clear Lake when I was down there in May. There were a couple of drakes on that shore but she was in charge of the brood. Aren’t they cute?

The young ducks become independent when they begin to fly and make forays out of their natal marsh about three weeks after that. They will join adult flocks in the fall to migrate1.

This past week I noticed a small group of Mallards swimming in a cove on the Sacramento River at Turtle Bay. They look to be juvenile ducks going through their molt into adult birds.

You can see that this young drake is beginning to attain the green feathering on his head, his breast feathers are mostly chestnut color but the central two rectrices of his tail are still straight, not yet showing the adult recurve.

This young female shows the plumage similar to the adult female but her bill is a solid yellow color with no hint of the dark spotted or saddled beak of the adult female.

Here is a close up of the young drake just beginning to get his characteristic green head feathers.

And a close-up of another drake showing how that iridescent head can look bluish or purple in the sunlight.

The Mallard is the most sought after and harvested duck in North America; in some years hunters harvest 20–25% of the autumn population, that harvest averaging over 4 million birds per year in the United States alone between 1979 and 19841.

Even taking these numbers into account, the Mallard population is considered stable. The concern is the use of lead ammunition by hunters and lead tackle by fishermen.

At least 75 wild bird species in the United States are poisoned by spent lead ammunition, including bald eagles, golden eagles, ravens and endangered California condors. Thousands of cranes, ducks, swans, loons, geese and other waterfowl ingest lead fishing sinkers lost in lakes and rivers each year, often with deadly consequences2.

For more information on the Center for Biological Diversity’s “Get the Lead Out” campaign, go here. To see more great bird photos, check out World Bird Wednesday!

References: 1Birds of North America Online, 2Center for Biological Diversity

Social Media Connect